Verify Your Downloads!

When we download software, we need to verify two things:

- The integrity of the software we have just downloaded.

- The authenticity of the package.

Checking these two things will ensure that the download went well, and that the software is authentic (and not malware, for example).

For the impatient, here is the process assuming that we have downloaded:

- A software package we want to use, in the example

software.pkg - A file containing the reference hash; in the example,

software.pkg.sha256 - A file containing the signature of the Software Author; in the example,

software.sig - The public keys of the Software Author; in the example,

author.gpg

$ sha256sum -c software.pkg.sha256 # 1. Check the download integrity

$ gpg --import author.gpg # 2a) Import downloaded public keys

$ gpg --keyserver hkp://<server> \

--search-keys <shortID> # 2b) Import public keys from a server

$ gpg --verify software.sig software.pkg # 3) Verify signatures

$ gpg --list-public-keys --with-sig-check # 4) If needed, check web of trust

These commands, why we run them, how they work, and how we should understand them, are discussed next. All the commands are Linux-specific, but information on Windows equivalents can be found in plenty of sites and I will probably write other post in the next few days.

Checking the Integrity of a Download

We want to check the integrity of a downloaded package to ensure that there were no transmission errors, and that nobody between our computer and the server exchanged the package for something else. We are checking that the download went well and we obtained whatever there was in the server: no more, and no less.

To do this, we verify the checksums of the files. Checksums are representations of the content smaller than the content itself, calculated by algorithms that ensure a stupidly small probability of two different files producing the same result. Some of those algorithms are members of a family called "hashes". Most useful checksums, and hashes particularly, always have the same length.

If there was a single bit of the file that got changed over the wire, the checksum calculated in our computer over the corrupted file would be different than the checksum of the server's file: the checksum wouldn't verify.

In order to calculate a checksum we only need the file itself, and the right program installed.

For example, if we go to the downloads page for VSCodium, a fully Open Source version of Visual Studio Code, we can see that for every package there is an extra file, ending in .sha256:

codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm

codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm.sha256

This extra file contains the reference checksum calculated over the server's file, and that is the exact same value that we should obtain in our computer from the downloaded copy.

The idea is to download both files to the same directory, and run the following command sha256sum -c over the checksums file:

$ sha256sum -c codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm.sha256

codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm: OK

What happened here is that the program sha256sum checked (-c) that the reference checksums present in the file codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm.sha256 could be calculated locally using the downloaded file. The .sha256 file content is the following:

75b9f844c22c98d4da33e64b6c7c49e8b4d0d94a438e4f8ce976e7e54b40a682 codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm

That line is a "properly formatted SHA256 checksum line", which is built by a SHA256 hash, two (2) spaces, and the name of the file the hash was calculated from in the server. From there, the check sha256sum -c performs is just to find a file that has the same name as in that line, calculate its SHA256 hash, and compare it with the first part of the line.

In this case the verification was complete and correct.

A file like that can have plenty of lines, not just one, and sha256sum -c will run all the checks in a batch.

Another possibility can be to have only the file to download, and the SHA256 line in the website, for you to see. In that case, we'd download the file and get the SHA256 locally by executing the sha256sum over the downloaded file, without -c:

$ sha256sum codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm

75b9f844c22c98d4da33e64b6c7c49e8b4d0d94a438e4f8ce976e7e54b40a682 codium-1.55.2-1618361370.el8.x86_64.rpm

That would give us the previously mentioned line, and we should just visually compare the hashes.

When the checksums are correct, we are sure that the download went well, but nothing else. It's up to us whether or not we trust that the publisher of the software is publishing authentic software, made by its true authors.

Checking the Authorship and Authenticity of the Software

If we don't trust the Software Publisher, that is to say, the website or the server we downloaded the package from, then checking the integrity of the download is not enough. The Publisher could have offered anything else in that file, and calculate a perfect valid reference checksum for a counterfeit package.

In such case of distrust, we want to check the software authorship, and therefore its authenticity. We can do that by obtaining a cryptographic signature of the package, created by the Software Author, and verifying it cryptographically.

There are many cryptographic signature mechanisms and algorithms, but here we will focus on signatures produced using asymmetric cryptography because they are the ones used most often, if not the only ones used to sign software.

In most asymmetric cryptography frameworks like PGP and GPG, the signature works as follows:

- A Software Author would have two keys: Private or Secret key, and Public Key. They are generated in the same process and they are inextricably linked.

- The Public Key is generally available; the Secret Key is never shared with anyone.

- Using their Secret Key, the software author produce a cryptographic signature, which in the case of PGP (or GPG), it consists in:

- calculating a hash, similar that the ones we've just discussed,

- signing the hash using the Secret Key and a cryptographic singing algorithm.

The idea of signing a hash and not the file itself is that a file can have a size from a few bytes to Gigabytes or Terabytes. By signing the hash, which is much smaller and has a fixed length, the result is produced in a predictable amount of time.

As the Secret and Public Keys are an inextricable pair, only the Public Key of the software Author will verify correctly the signature produced with the corresponding Secret Key. As the Public Key is made available, everybody can verify the signatures using the right software.

Here's what we need to do to check a signature with a real example, a Manjaro GNU/Linux ISO file.

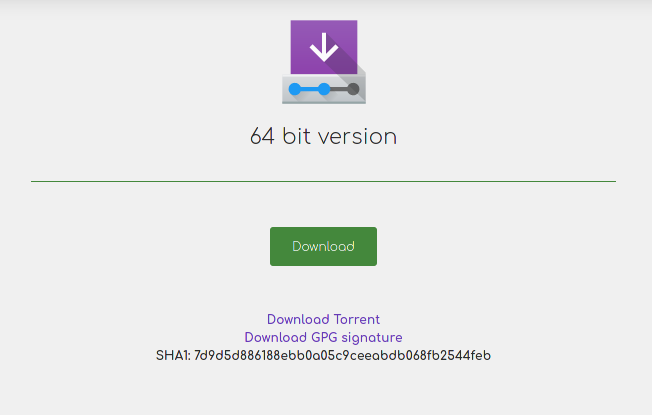

First: Download the software from an, in principle, trusted server. In this case, we will download a file named manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso from the Manjaro XFCE download page. This file has an associated GPG signature that we will also download, manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso.sig, and a SHA1 hash printed in the web page, 7d9d5d886188ebb0a05c9ceeabdb068fb2544feb.

Second: Check the hash as we discussed earlier in this post, to make sure that the package is uncorrupted. In this case we need to compute the hash and compare it visually with the reference one, present in the download page.

$ sha1sum manjaro manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso

7d9d5d886188ebb0a05c9ceeabdb068fb2544feb manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso

It verifies, so let's go with the GPG signature.

Third: For us to be able to verify a GPG signature, we first need to obtain the public keys of the Software Author. In this case, Manjaro offers two sets of public keys, the general Manjaro ones, and Philip Müller's, "just in case we didn't trust the server where Manjaro made the general keys file available". That statement is a bit of food for thought that we'll discuss later, and a good example because it shows two ways for obtaining public keys.

First, we download and import the Manjaro general keys.

$ wget https://[url to the manjaro keys]/manjaro.gpg -O manjaro.gpg

$ gpg --import manjaro.gpg

On April 28th 2021 this imported 22 keys into the keyring, allowing us to verify packages signed by several people and machines at Manjaro.

To download Philip Müller's keys from a public PGP Key Server, use the following:

$ gpg --keyserver hkp://pool.sks-keyservers.net --search-keys 11C7F07E

gpg: data source: http://194.95.66.28:11371

(1) Philip Müller (Called Little) <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

2048 bit RSA key CAA6A59611C7F07E, created: 2012-05-05

Keys 1-1 of 1 for "11C7F07E". Enter number(s), N)ext, or Q)uit > 1

gpg: key CAA6A59611C7F07E: "Philip Müller (Called Little) <REDACTED@manjaro.org>" not changed

gpg: Total number processed: 1

gpg: unchanged: 1

Note that Enter number(s), N)ext, or Q)uit > is an actual prompt and we have to select the key, 1 in this case. Pay attention to the CAA6A59611C7F07E part: is an identifier for the key. Another thing to note is that the string we used to search the key (11C7F07E) is part of the key identifier. The lower part of a key's ID is often referred to as "short identifier of the key" for obvious reasons.

The keys can also be searched by some other identificative fields, for example an email (real email omitted for privacy reasons!):

$ gpg --keyserver hkp://pool.sks-keyservers.net --search-keys "REDACTED@manjaro.org"

gpg: data source: http://194.95.66.28:11371

(1) Philip Müller (Called Little) <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

2048 bit RSA key CAA6A59611C7F07E, created: 2012-05-05

...

The key ID identifies the pair of keys, not just the Public Key. It is important to know the ID of key pair, as it is the only way to really identify a key used to produce a signature and therefore the key needed to verify it. There can be many keys for a single email address, not all of them legit. The way to know the key needed to verify a signature is try to verify it without importing any key, as it will output the ID of the key pair that was used:

gpg: Signature made Mon 19 Apr 2021 18:47:28 AEST

gpg: using RSA key 3B794DE6D4320FCE594F4171279E7CF5D8D56EC8

gpg: Can't check signature: No public key

Fourth: If the download of the iso verified the hash on previous steps, then check the signatures:

$ gpg --verify manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso.sig manjaro-xfce-21.0.2-210419-linux510.iso

gpg: Signature made Mon 19 Apr 2021 18:47:28 AEST

gpg: using RSA key 3B794DE6D4320FCE594F4171279E7CF5D8D56EC8

gpg: Good signature from "Manjaro Build Server <build@manjaro.org>" [unknown]

gpg: WARNING: This key is not certified with a trusted signature!

gpg: There is no indication that the signature belongs to the owner.

Primary key fingerprint: 3B79 4DE6 D432 0FCE 594F 4171 279E 7CF5 D8D5 6EC8

In this case, the signing key was one of the keys present in the file manjaro.gpg, the one for the Manjaro Build Server with identifier 3B794DE6D4320FCE594F4171279E7CF5D8D56EC8. The verification process was correct, so we need that something called Manjaro Build Server is the creator of the ISO we've just downloaded.

Fifth: If we want to check the authenticity of such Manjaro Build Server dude, we can do so by validating its key using Philip Müller's key (provided we trust him). That can be done by check the web of trust for Manjaro Build Server key, and see whether Philip is part of that web of trust. For this one, issue the following command:

$ gpg --list-public-keys --with-sig-check

Within the output of this command we can see all the public keys we have in our keyring, and who has signed them. Signing a Public Key with your own secret key is, in this context, the ultimate vouching act. In the case of the Manjaro Build Server, which we can identify by looking at its identifier, we can see that within its signers there is Philip Müller (the ID is the same previously imported CAA6A59611C7F07E):

pub rsa3072 2020-10-28 [SC] [expires: 2022-10-28]

3B794DE6D4320FCE594F4171279E7CF5D8D56EC8

uid [ unknown] Manjaro Build Server <build@manjaro.org>

sig! 8238651DDF5E0594 2020-10-29 Matti Hyttinen <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

sig! DAD3B211663CA268 2020-10-29 Bernhard Landauer <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

sig! 084A7FC0035B1D49 2020-10-29 Dan Johansen (Manjaro) <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

sig! CAA6A59611C7F07E 2020-10-29 Philip Müller (Called Little) <REDACTED@manjaro.org>

sig!3 279E7CF5D8D56EC8 2020-10-28 Manjaro Build Server <build@manjaro.org>

sub rsa3072 2020-10-28 [E] [expires: 2022-10-28]

sig! 279E7CF5D8D56EC8 2020-10-28 Manjaro Build Server <build@manjaro.org>

Therefore, if we trust Philip Müller, we can trust the downloaded ISO signature because Philip has endorsed the Manjaro Build Server by signing its key with his own.

Package Managers

The above process is what we need to do for the software we download manually, from the web.

Package Managers for GNU/Linux, as apt, pacman or yum among others, for Windows as Chocolatey, and for macOS as homebrew, should do all the avobe automatically, transparently and by default. Check the documentation of the system and package manager you use (and trust) to check specific details.

This is All About Who We Trust

If we pay attention to how this works, we'll se that all this is about trust. There is no technique that would give us 100% certainty of the authenticity of a software package. We need to judge if we trust the Software Publisher, and if we trust the Software Author, and if we believe their public keys really belong to them --the actual persons or companies. Check after check, we are traversing a web of trust that is effective as long as we can find a point we can trust.

Further Reading

A good introduction of the web of trust, and links to further material, can be found in the Wikipedia.

More on the cryptographic suite used by most software publishers, authors and distribution channels can be found in the GNU Privacy Handbook.